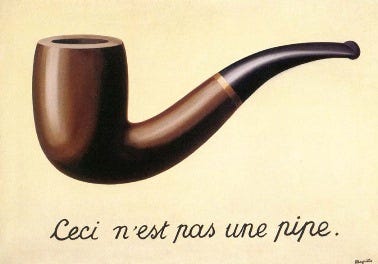

Magritte's pipe

You might be familiar with this painting: It depicts a curved wooden smoking pipe, brown wood with a black mouthpiece, and shading indicating a light source on top and to the left of the pipe. Underneath the pipe is written "Ceci n'est pas une pipe"—This is not a pipe. It is called a "surrealist" painting, but on first glance it looks quite realist: The dimensions, size, lighting and shading, colors... it's not quite photo-realistic, but it's clearly a pipe.

So why does Magritte claim this is not a pipe?

Most people's first reaction (and mine as well) to this seeming contradiction is to challenge it: Of course it's a pipe! It's certainly not an elephant, a cement block, a hydrogen atom, a space alien, or any other of the uncountable number of things in the universe.

The retort to this reaction is that it is not literally a pipe. It is paint on a canvas (or, more likely nowadays, pixels on a screen); a two-dimensional depiction of a pipe. But it is not actually a pipe. You cannot put tobacco (or anything else) in it, light it, and smoke it. You cannot take it out of your smoking pouch in a cigar shop and pretend to be a sophisticated hipster when you actually look like someone desperate for attention. And you can do things with the digital version of that painting that you cannot do with a real pipe, like zoom in until it becomes pixelated, change the colors, and other fun Photoshopy things.

What is a pipe?

OK, so the picture is not literally a pipe; it depicts a pipe. It represents a pipe. Fair enough.

But what exactly is a pipe? Is there some prodigal pipe that exists somewhere in the Platonic plane, and all physical pipes are derivations of this pure pipe?

No, I don't think so. (I was tempted to write "obviously not," but I don't think it's obvious. We don't understand the nature of reality well enough to know with 100% certainty that there is no platonic realm that contains a pure pipe. But such a concept does seem unlikely, so I will proceed under the assumption that it is not the case.)

How many pipes have you seen in your life? I guess it's in the range of hundreds, possibly a few thousand. All of the pipes you've seen—and all the pipes you will see for the rest of your life (which I hope will be long and healthy and happy) share some features that make them "a pipe." You know, having a bowl to put the tobacco in, some tube-like extension, and a nozzle to put into your mouth to inhale the smoke. Individual pipes will have different shapes, weights, colors, patterns, and so on. But they all share some structural design features that allow them to be used for the purpose of burning something in order to inhale the smoke.

The point is that there are myriad instances of individual pipes, but each one is a pipe; there is no the pipe.

And this in turn means that the pipe is a concept. It exists in our brain as some pattern encoded in the physical structure of the brain, and when we see a physical thing, we can easily determine that it is a pipe.

Where is The Pipe?

Here's the question I'm building towards: If all humans suddenly disappeared, would pipes still exist?

The millions of physical pipes that we have manufactured would, of course, continue to exist. Those are solid arrangements of matter that are still there when we put them into cupboards, the trashcan, or just look away from them. Sure, eventually they will cease to exist: Some day the sun will explode and vaporize the Earth and all the pipes with it. Perhaps before then, the pipes will break down or be digested by some bacteria that has evolved to convert man-made materials into their elementary compounds.

But are those physical things still "pipes" after we're gone? It's a question of where the concept of the pipe exists. If the concept exists only in our brains, then when our brains are gone, the concept no longer exists. Or has the concept of the pipe been somehow written into the universe because it had existed in our brains? The brain is a physical thing that exists, and so if a concept comes from a physical thing, then must it also be a physical thing?

Perhaps you might argue that the concept is a physical thing while we are alive, but it ceases to be a physical thing when we all die. But I'm not sure it's so simple. Stars are plentiful in the universe, but if the universe continues expanding, then there will be a time when stars no longer exist. (Don't worry, it won't happen in our lifetimes.) But at that time, stars will have existed, even if they don't exist at that moment. So maybe the concept of a pipe will — somehow — exist in 100 trillion years from now, even if there are no more brains to encode them.

Back to the pipe

Does any of this matter? I don't think so. We can each live to be 1000 years old and live happy, meaningful lives without ever scratching the surface (literally and figuratively) of Magritte's painting, beyond the direct interpretation that an artistic rendering is not the same thing as the actual physical object.

I'm not sure how deep Magritte intended us to go with his seemingly contradictory painting. But it made me think, and I suppose that is enough for art to be successful.

Thanks. Your musing made me feel less lonely....nice to know that other people are thinking too....

Professor, what you said about Magritte’s pipe struck me hard. The painted pipe is not a real pipe, but a representation. That immediately reminded me of something I’ve been wrestling with: whether concepts like “pipe” are only brain-born human constructs, or whether they exist as deeper patterns of necessity in the universe.

Tis is how I see it: the "concept" of a pipe—as a resource transmitter—will outlive the human species. It may already have existed before humans, as a structural necessity of flows: rivers carving channels, roots carrying sap, stars funneling plasma. The concept is more fundamental than the material instance.

Our "means" of doing things change, but the "concepts" guiding them seem to persist:

1. Communication survives all its vessels. Whether through vocal cords, jungle howls, pigeon legs, letters, telegraphs, smartphones, synthesizers, DNA, C++ codes or even atomic patterns—the "concept" of information transfer outlasts every medium.

2. Energy extraction: adapts its clothing. From chewing plants to eating meat, to burning coal, to splitting atoms, to drawing from pulsars or black holes, the "concept" of pulling usable power from the environment never dies, only retools.

3. Storage: morphs endlessly. From skin bladders and clay pots to lakes, dams, planets with thick atmospheres, or black holes—the idea of "holding a resource" survives each container.

4. Killing perils: reinvents itself. From stones, knives, and rumors, to vaccines, debugging corrupted code, or even cosmic-scale weapons—the "concept" of neutralizing threats always finds new instruments.

So yes, the material dies, but the concept outsurvives.

This also ties into the Lindy effect. If a concept has endured for 20 years, odds are it’ll last at least 10 more. If it’s lasted 2,000 years—like Bible, Pythagoras’ theorem, Euclidean distance, Zeno's paradox extending to limits in calculus —it’ll probably last 2,000 more. If it’s 10,000 years old—like agriculture, family structures, or monogamy—it likely has 10,000 more ahead of it. Survival of abstractions seems proportional to their historical weight.

So maybe Magritte was right in a narower sense: the image of a pipe isn’t a pipe. But there’s a bigger truth—that the concept of “pipe” is more real than any pipe, because it survives pipes. And it will continue to, with or without us.